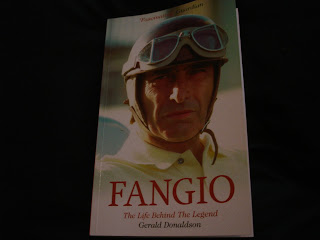

Furthering my campaign to revisit some of the motorsport-related titles residing on my dusty bookshelves, I recently re-read Gerald Donaldson's 2003 biography of the great Argentinian driver, Juan Manuel Fangio.

Fangio still holds a special fascination and a particular aura, matched perhaps only by those of Ayrton Senna, although they were quite different people. Fangio was revered by his peers, and still represents something of a benchmark, as much for his human qualities as his consummate skills behind the wheel of a car.

His upbringing was in stark contrast to that of today's stars, and indeed to most of his contemporaries. In addition, his racing apprenticeship was unusual, and may have helped to equip him with the qualities which separated him from his competitors when he embarked on his international career.

The early chapters are an intriguing window on the world of the early twentieth century, when motor vehicles were still a relative novelty, and in the infancy of their technical development. The picture which emerges is of an early life characterized by the inculcation of certain imperatives, such as the importance of hard work. Even the early years suggest Fangio's hallmarks of mechanical sympathy, adaptability and resourcefulness.

A crucial part of the story is Fangio's participation in the epic South American road-race marathons. The author unfurls evocative accounts of the sheer scale of these undertakings, the hardships which were undergone, and the perils and hazards which confronted the competitors. The range of emotions and environments which he encountered must have been character-building. Describing the dramas, the surroundings and the sensory experiences is a strength which is noticeable in some of Donaldson's other books, and those skills are well employed here.

This biography paints a picture of the tenor of an epoch, where improvised machinery and improvised racing schedules were the norm. Also, the comradeship and friendly spirit which prevailed among the drivers throughout comes across strongly.

Fangio seems to have been a self-made man, also self-taught to some extent. From humble origins, a strong work ethic had helped to instill a resilience of character which was crucial to his success. The author does not portray the man as some kind of saint, but his flaws and weaknesses were evidently less pronounced than those of most people, and a practical, pragmatic approach served him well. It also appears to me that Fangio combined old-fashioned virtues with the more entrepreneurial spirit of modern times. A more complex individual than is sometimes made out, perhaps.

The book contains some interesting material on that "lost" period between the end of the Second World War and the 1950 inception of the World Drivers' Championship. It is sobering to be reminded of the frequency of fatalities and serious injuries back then, both to competitors and spectators. The stories of the Grand Prix races are related entertainingly but sparingly, and they capture some of the essence of what was still a "heroic" age. Indeed, some might contend that the "heroic age" came to a close when Fangio retired from racing.

There is a little insight into Fangio's character, and his philosophy of life, via quotes and anecdotes. These focus on his means of coping with danger and challenges, and with the nature of competition. An element which permeates these pages is just how much physical discomfort the drivers of that period had to withstand, whether through primitive, ill-handling machines or via the elements. Comfort was still some way in the future.

This biography is compact and balanced, although I don't think it is quite as fluent and impressive as the author's books about Gilles Villeneuve and James Hunt. It will, however, enthuse the reader about the man and the era in which he competed so ably and nobly.

No comments:

Post a Comment